First and foremost: I feel like this collection of thoughts is even less put together than what I would’ve said in class today…but it’s the thought that counts so we’ll just run with it here.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the poem “Mental Cases” that we read aloud and discussed in class this morning. Specifically, I’ve been thinking a lot about the half meaning of some of the lines.

Let me enlighten you with my thought process:

I come from a family of scientists (my mom is a computer scientist, my uncle was an aerospace engineer, etc. etc.) so science is often on my mind. So, in class today when someone spoke about how young many of the soldiers were, I started thinking about Paul in All Quiet when he was talking about how he had nothing to go back to since his life hadn’t really started yet. He’d only really lived half of it.

There. There it was. The connector. Paul’s half-life.

I hate when people do this, but I’ll do it just for clarity:

Half–life means the time required for one half the atoms of a given amount of a radioactive substance to disintegrate.

The first part of Paul’s life was the build-up to war. The second part was his part in and his comedown from it. Half-life. Half-life. Half-meaning.

So now we’ve arrived at the real point of this post (it is a very difficult task for me to collect my thoughts apparently): the half meaning of some of the lines in “Mental Cases.”

Owen gives us the following for the first stanza:

Who are these? Why sit they here in twilight?

Wherefore rock they, purgatorial shadows,

Drooping tongues from jays that slob their relish,

Baring teeth that leer like skulls’ teeth wicked?

Stroke on stroke of pain,- but what slow panic,

Gouged these chasms round their fretted sockets?

Ever from their hair and through their hands’ palms

Misery swelters. Surely we have perished

Sleeping, and walk hell; but who these hellish?

I was really intrigued by the six bolded words. Especially when read together.

Shadows relish wicked? Panic sockets palms? Both really reminded me of the hollowness associated with war.

Like we discussed in class today, shadows are that purgatory state between being tangible and tangible. They’re like the people in charge who send others to war but never fully participate themselves. The shadows, or in this case, those in power relish the wicked because the wicked (essentially war) is a profit machine.

Panic sockets palms? The fear those in power face force them to enlist bodies–tangible bodies–to fight for them.

We see similar half-meanings in stanza 2 with:

–These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished.

Memory fingers in their hair of murders,

Multitudinous murders they once witnessed.

Wading sloughs of flesh these helpless wander,

Treading blood from lungs that had loved laughter.

Always they must see these things and hear them,

Batter of guns and shatter of flying muscles,

Carnage incomparable, and human squander

Rucked too thick for these men’s extrication.

Murders witnessed wander made me think of the people who just narrowly escaped the tolls of war.

Muscles squander extrication? The powerful effects of the government, propaganda, and the socialization of people at the time denied any real chance for a freedom from the war.

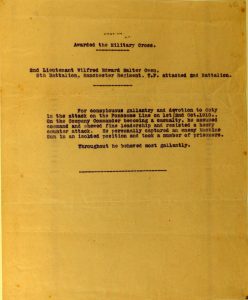

Maybe this is all reading too much into things. Maybe this is all so heavily influenced by the documents we read at the beginning of class where Owen wrote

“On behalf of those suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practiced upon them.”

But I’d like to think it’s not. I’d like to think these half-lines were intentional. I’d like to think that the meaning I found in them had some value.

UPDATE: lol I’m just now realizing half-meaning is not at all what I’m talking about but…umm…you get the picture.