What was your favorite piece we read this semester? Why?

Or, what is something you didn’t expect to learn in this class, but did?

Or! What was the most shocking thing we talked about, read, or found this semester?

What was your favorite piece we read this semester? Why?

Or, what is something you didn’t expect to learn in this class, but did?

Or! What was the most shocking thing we talked about, read, or found this semester?

I think (just generally) we look at war as this abstract thing that happens when in reality I don’t think it is. People send other people into war.

In class today, we repeated the question, “Is this enough?” Was it enough to offer up the coffee? Was it enough for the narrator to lie to the blind man? What is enough?

Focusing in so much on this question really got me thinking about the juxtaposition presented in the text that we all seemed to be missing. Yes, the narrator may have been offering some form of salvation to the man, but at the same time, the very nature of her job is to bandage the wounded and send them back into war. Fix them and send them to die. We’re faced with this huge dichotomy. How can we choose to see something as a sign of warmth and salvation, and shield ourselves from the inherent coldness presented?

Is the nurse’s actions a sign of humanity? Or does it just function as a way to even the playing field?

Further (and to relate this question to some of the other texts we’ve read this semester), it seems as though war literature forces us, as consumers of their messages, to view war un-abstractly. We saw this in All Quiet with the suggestion of getting only the people in power to fight as well as in some of the other books we’ve read.

I guess my question is, were the nurses actions meant to restore this faith in humanity or was it intended as sarcasm? Are we meant to view war abstractly as an entity that just happens? Or not? Are we supposed to see war as inevitable? Or as something we have a hand in continuing? How much of a hand do we actually have in continuing war?

Today in class we were discussing mythical language and the angels in the short stories we read for today. The discussion made me think of how Paul and Nellie didn’t want to talk to those at home about their war experiences or show off that they had really “been in it”. Paul made up stories or told half truths in order to please his dad and the people back at home without damaging himself with the truth. The short stories and poems talking about the angels and visions of dead Germans may not be factually true but they are as much of the truth as the soldiers can tell and therefore become the truth for those at home. The “true” stories of the angels in the battlefield spread and become fact. The feelings in those stories could actually be true; the soldiers could have felt as though the strategies or weapons they were told to switch to could have felt like divine intervention or guardian angels saving them from death.

I was really interested in the idea brought up in class about “there’s nothing left for Paul to sacrifice for.” The whole time we were discussing it, I couldn’t help but think that I’ve heard that idea before (in some capacity at least) relating to WWI. It wasn’t until I sat down in my next class (I’m frantically trying to type this before my professor arrives so please excuse the brevity) that I realized what it was. No Man’s Land. Paul having nothing to sacrifice for was a metaphorical reference to a literal part of the war–No Man’s Land.

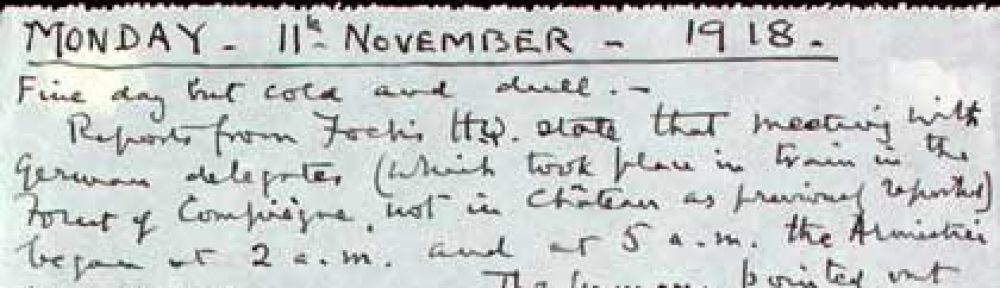

I found that the photo above elaborates a lot on this point. As the war goes on, this area becomes more and more degraded and we can look at this as a metaphor for Paul. The longer he is involved in the war, the more his mind deteriorates. He becomes the war.