What was your favorite piece we read this semester? Why?

Or, what is something you didn’t expect to learn in this class, but did?

Or! What was the most shocking thing we talked about, read, or found this semester?

What was your favorite piece we read this semester? Why?

Or, what is something you didn’t expect to learn in this class, but did?

Or! What was the most shocking thing we talked about, read, or found this semester?

I thought this might come up in class on Tuesday. Since it didn’t, I thought I’d post about it here.

I’ve always been sensitive to the intensity of certain scenes in books, movies, even training videos. Most people take “sensitive” to mean I get upset easy, or I’m squeamish. And, while I have been brought to tears, once or twice, (damn you, King’s Green Mile!), I think my strongest reaction is what most would call “squeamish.” Though, to me, it differs a little.

No, I am not a fan of the modern “gore fests” that we now call horror movies. Never was a fan of seeing that which should be on the inside of the body, on the outside. But it isn’t the blood, or the gore, that bothers me. I cook! Death is all present in the kitchen.

It’s the pain. It’s the intensity of the emotions connected with the situation. Ironically, many of the situations, of urgency, have an aspect of medical – life or death – involved.For instance, in high school, I passed out (quietly, unbeknownst to everyone else) at my table while watching “Saving Private Ryan.” The scene that was too much for me involved the medic describing to the men how to give him morphine, how to stop the bleeding, and so on. Sure there was blood and, sure, it was a lot. But I -KNOW- it’s not real. Somehow, though, my brain doesn’t realize the same thing about the emotions, or the urgency of the scene.

I say all of this because even before reading, “In The Operating Room”, I expected that I would need to be on guard. Something about doctors, hospitals, and the things that go on there (needles!) just put me on edge. So, when I got to the third page and started feeling that fuzzy feeling creep up… I was no longer just reading the story but placing myself in it, and trying my hardest not to imagine what it would feel like to have a doctor amputate my leg, during that time period.

I paused for a bit on that third page. I tried to push on, however, and that feeling came back a bit too quickly for my liking. I did not want to pass out, in the foyer of GCC, in public.. at all. Instead, I penned this little reaction, before I decided to go on. I couldn’t get far enough from the scene, couldn’t get away from the reality.

And, it struck me.. of all the things we’ve read, this is the only one to cause such a strong reaction from me. And, not even about the real carnage of what took place on the front lines, the body parts in ambulances, nor the disfigured men that would never be the same.

It’s this scene where the doctors are talking about the patients as if they were just body parts, as if they are lost causes, about blooding spurting through the air that makes me fuzzy and light headed. Weird.

So, how about any of you? Were any of you affected by any of the stories we’ve read enough to cry? Or to stay up late wondering how anyone could withstand those conditions? Anything more than the expected, “Wow, that was rough?”

For my Website Recon, one of the sites I went to discussed how men who’d had their faces reconstructed, despite surgical success, still could not get past the trauma. They would still hide themselves away or be too ashamed to be around their friends and family.

“The Beach” reminded me greatly of this. While the man in the story has had an amputation, he still finds it hard to be around his wife and reconciling what has happened to him. He can’t stand to be around her- almost disgusted by her perfection- but at the same time he doesn’t want to lose her. It’s interesting to get this kind of POV– aside from Nellie’s fiance, I don’t think we’ve seen the inner thoughts of a wounded soldier in these novels. Henry was wounded, but he made a full physical recovery and was sent back to the front. I doubt the soldier in “The Beach” is going anywhere any time soon.

What do you all think Borden was trying to do by providing this point of view?

Today we talked in class a lot about the perspective of the speaker in Mary Borden’s collection of stories in “The Forbidden Zone”. I don’t want to talk much about this because we talked for a while in class about it and some other people (like Jordan in her post here and Jamie in her post here) have already extended this discussion onto the blog. I will, however, post the pictures of the drawings my section produced on the board today. I’m curious as it if there were any other perspectives that you saw the speaker holding in any of these stories that were different than the ones talked about in class. I personally saw the speaker as an onlooker or witness to the events, almost as a distant storyteller, which makes sense being as she is telling us these narratives in a very story-like way.

One thing that really struck me as I read through the selection of work for today was the personification of things like the town and aeroplanes. The planes, in particular, caught my attention because they are the machines that are doing the destroying (unless you argue that man is the machine and the planes are just their way of executing but that is a whole other idea) but yet their characterization is almost childlike. They seemed like toys to me, in some really odd and warped way. What do you think this personification is doing in this work? What is the purpose of it? Did you even notice it while initially reading for today?

Another thing that I really liked when it came to Borden was her style. We talked a little bit about her sentence structure and what that was doing in the pieces, along with the repetition. Not to be repetitive, but I really loved the repeating. The four paragraphs that we read aloud in class today (pages 23 & 24) had a sort of systematic repetition happening there. In the first paragraph, in the first few sentences, one work from the first sentence would be repeated into the second, and from the second another word would find its way into the third and so on. This choice of subtle repeating seemed like it was trying to lull the reader or pull them through the paragraph. The lulling also happens towards the end of the first paragraph as sentences begin to establish a rhythm and rhyme to them. How do you see these poetic devices working in a non-fiction piece? Where there any other patterns that you noticed while reading? Or where there any other stylistic choices that Borden made that you think should be recognized here that we missed in class today?

I know some of these questions can be more analytical and maybe you need something easy to think about since we are just out of midterms week, so I will leave you all with this: out of all of the stories we read for today, which one was your favorite and why? Or, if you don’t want to be too specific, or don’t have a favorite, how do you feel about Borden in general? Do you enjoy this type of reading more or less than the novels and poems we have already tackled this semester?

I think the point of literature is to encapsulate the human experience in any way it can, but, as we talked about in class, I often feel conflicted about who can write about what and how authentic the encapsulation of the truth is. In the words of Prof. Rochelle, all text stems from an initial truth. At what point though are we willing to accept an authors’ credentials but deny the experiences they write about?

I think collectively we’ve agreed that Not So Quiet, even though it has been written by someone who never first-hand experienced the war, was based so much on personal experience, that we approve of it as an accurate retelling of the war. With The Forbidden Zone, we’ve read in the author’s note that the broken retelling is a stylistic representation of the war, and we can inherently agree that the text is an authentic one. But are books like A Farewell to Arms that lie so heavily in a fictional story-line, authentic and as worthy of telling as the others?

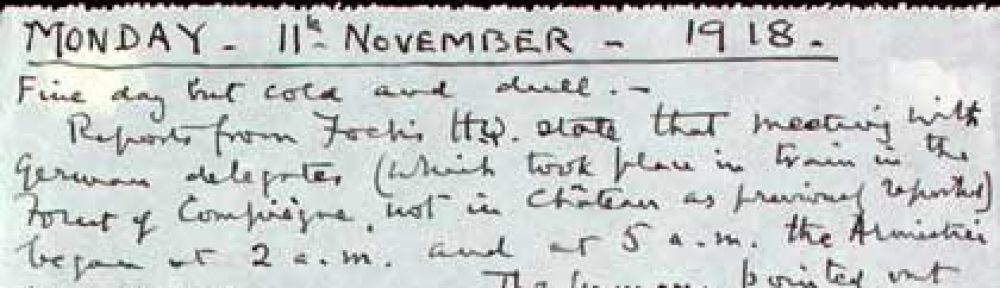

Something that I noticed has been a major theme in many (if not all the books) has been the worth behind the war, or rather, the lack thereof. I think we saw this especially on page 24 of the Borden text. On that page the General is speaking all about how these men will die before they ever so much as get the chance to return home. Much like how all sides knew before Nov. 11, 1918, that the war would end, it seems as though the deaths of these men is worthless. That any aspect of this war up until this point in the texts we’ve read and so on has been worthless, and it was this worthlessness that reminded me of the Tennyson poem The Charge of the Light Brigade. I’ll include the first part of the poem below:

IHalf a league, half a league,Half a league onward,All in the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.“Forward, the Light Brigade!Charge for the guns!” he said.Into the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.II“Forward, the Light Brigade!”Was there a man dismayed?Not though the soldier knewSomeone had blundered.Theirs not to make reply,Theirs not to reason why,Theirs but to do and die.Into the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.IIICannon to right of them,Cannon to left of them,Cannon in front of themVolleyed and thundered;Stormed at with shot and shell,Boldly they rode and well,Into the jaws of Death,Into the mouth of hellRode the six hundred.